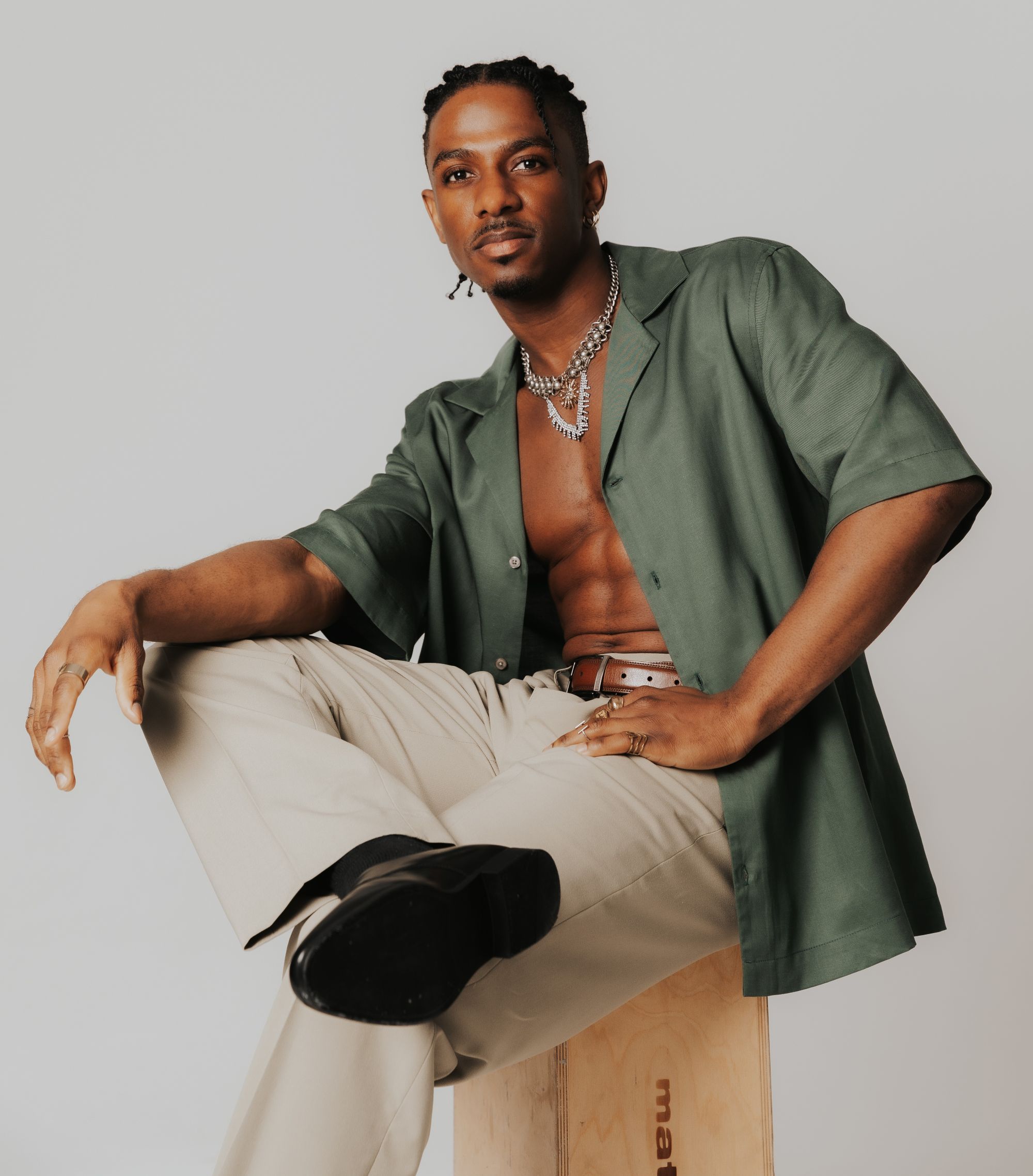

When Jay Mills walked onto the Super Bowl field for halftime, the scale of it hit differently than any “big crowd” he had faced before. What made it surreal was not only the stadium, or the production, or the fact that millions were watching from home, it was the meaning. In his mind, the performance carried a message shaped by the current state of the world, and that combination, art plus moment plus audience, made the experience feel especially weighty.

For people on St. Maarten, seeing a local professional dancer moving at the center of a global spectacle was pride in real time. For Mills, it was also a reminder of what he had to build without the usual safety nets, and why the conversation back home cannot stop at applause.

The island that formed him

Long before the lights and cameras, Mills’ foundation was local, personal, and communal. His formal training began at INDISU Dance Theatre, but his education as a performer was bigger than any studio. Growing up on St. Maarten put him in constant proximity to a dance community that felt like family, and it gave him repeated chances to perform, from his high school stages to Youth Extravaganza and countless other events. Each one fed something essential, the love of dance itself.

Programs like Indisu expanded that love into range and technique, exposing him to different disciplines and new ways of learning. Just as important, the island environment demanded that he stretch past what was readily available. That push, he says, taught him humility, discipline, and a stubborn kind of determination, the kind that turns a private vision into a real plan.

When the teacher is a screen

Mills’ story is not only about talent. It is also about a familiar Caribbean reality, the gap between desire and access.

At different points, he faced limited resources locally, especially for specific street styles that fascinated him. Rather than accept the limits, he went where the lessons were, on YouTube, training himself in popping and locking. At the time, he did not frame it as some heroic grind. He simply wanted to dance every day, and he wanted to grow.

That period taught him something that cuts through motivational clichés because it is so plain. When you love something unconditionally, you will do what you have to do. What looks like discipline from the outside often begins as obsession and curiosity, then becomes resilience because there is no other option.

One week that changed the ceiling

There are turning points that do not arrive with trumpets, they arrive as exposure.

For Mills, Art Saves Lives was one of those moments. The experience put him in professional training with New York based artists before he eventually moved to New York City. He describes that week as life changing, dancing from morning until night, learning from dedicated educators, surrounded by talented dancers from across the island.

In just one week, he felt himself grow more than he could have imagined, and the message landed with clarity: with sustained access to that level of training, he could take his dancing as far as he aspired to take it. The point is not only that he improved. The point is that the ceiling moved, and once a ceiling moves, it becomes hard to pretend you cannot reach higher.

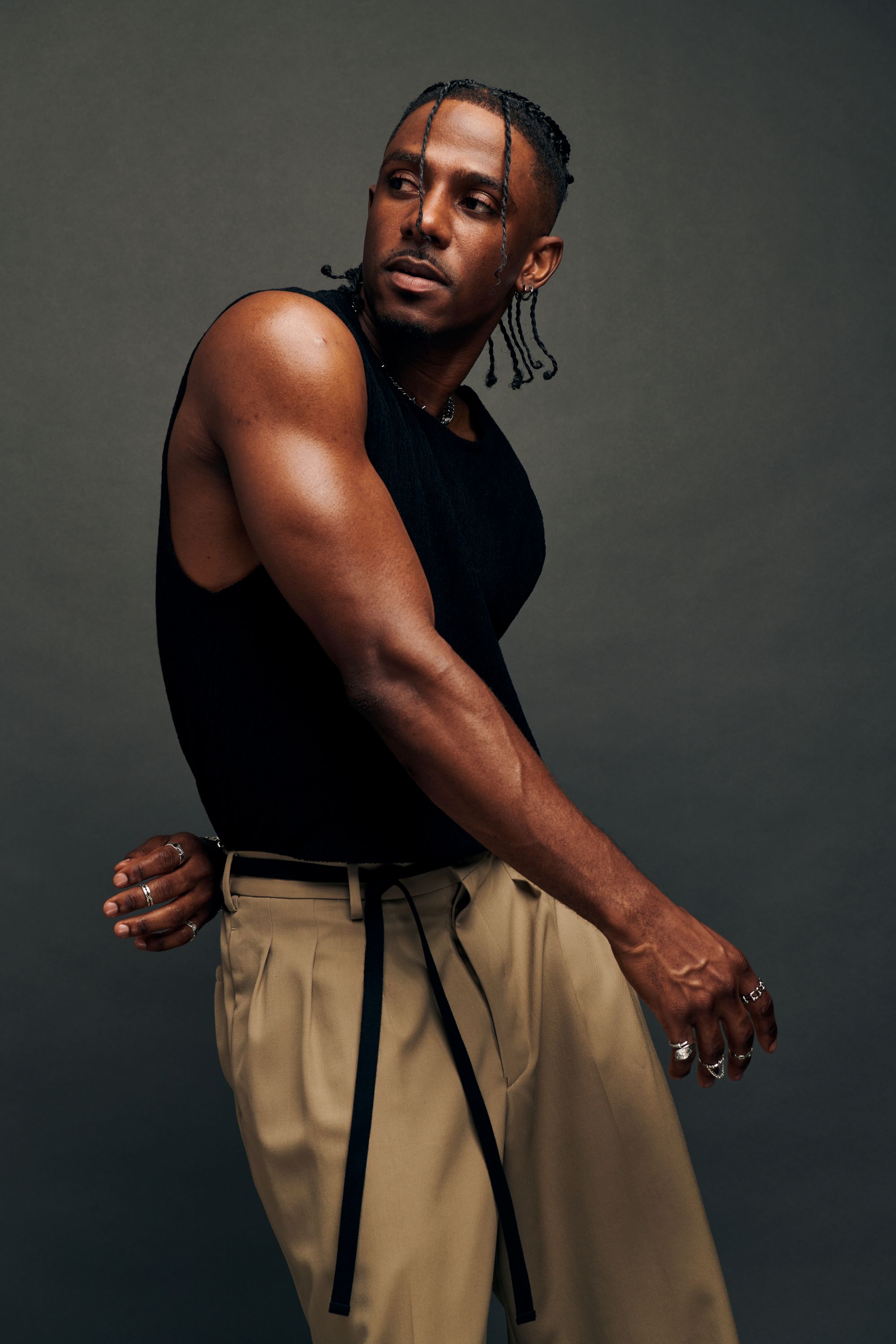

The hidden pressure of becoming “the choreographer”

People often talk about careers in the arts as if the breakthrough is the finish line. Mills describes something more complicated, dancer and choreographer rising at the same time, with a new kind of pressure following the title.

The hardest transition, he says, was realizing that being a sought after choreographer is not just teaching steps. The job expands into leadership. He is responsible for guiding other dancers, helping them grow in their personal journeys and as professionals in the industry. What he creates can shape someone else’s path, and he treats that influence as both privilege and responsibility.

That framing matters for St. Maarten’s creative ecosystem, because it challenges a common misunderstanding: investing in one artist is not only about one artist. When a dancer becomes a working choreographer, they become infrastructure, a moving school, a standard, a bridge for others.

Representing home, always

After the Super Bowl performance with Bad Bunny, St. Maarten’s Minister of TEATT, Grisha Heyliger-Marten, called the moment proof that the island’s people are among its greatest ambassadors. Mills does not treat that as a slogan. He treats it as a discipline.

He says he never forgets where he comes from, or the influences that made him who he is. Born in Jamaica and raised in St. Maarten, he carries his roots into every professional space. He shares his story and culture, and he makes the invitation directly, encouraging people to visit St. Maarten to experience its beauty, creativity, and spirit for themselves.

Ambassadorship, in this sense, is not a flag moment. It is repetition. It is the refusal to become anonymous.

The hard question behind the applause

If the story ended with “local dancer makes it big,” it would be easy to celebrate and move on. Mills refuses that comfort.

He argues that the biggest difference for emerging talent on the island would be support and acknowledgment, especially from government. Too often, he says, art is treated as unimportant, as if it has no significant impact. He points to a pattern that many creatives recognize: artists from St. Maarten can represent the island abroad for years, yet they are praised only after collecting a certain number of accolades, or after reaching major milestones overseas. He calls that approach backward, because praise, support, and acknowledgment should come before those achievements, not after.

His critique is practical: if the island wants current and emerging talent to thrive, it needs greater government support, and it needs businesses willing to sponsor events that cater to artists.

This is where the pride of a Super Bowl appearance becomes thought provoking, because it forces an uncomfortable comparison. St. Maarten is quick to feel proud when the world claps, but what does St. Maarten fund, build, and celebrate when the world is not watching?

A blueprint, not a complaint

Mills does not stop at criticism. He proposes clear steps that are specific enough to measure.

One major idea is a performing arts center, a central hub for workshops, rehearsals, and public performances. In his view, that kind of space would nurture local talent while providing the structure needed for artistic development.

He also calls for public recognition that is visible and consistent, celebrating artists for exceptional achievements locally and abroad. He imagines artists featured on billboards, on posters throughout the island, and at the airport. Visibility, he argues, makes creatives feel represented and valued, while also showing visitors the people carrying St. Maarten’s name into regional and international spaces.

This is not only about ego. It is about signaling what a country respects. Countries advertise what they want more of.

A message to the unseen

For young creatives who feel unsupported, Mills does not offer fantasy. He offers the kind of encouragement that comes with a warning label, it will cost you something.

He tells young artists that hard work, discipline, and consistency never go unnoticed. He also names the price, sacrifices, doubt, struggle, patience. Then he insists on the outcome, sooner or later, dedication pays off, and the work you poured your heart into opens doors you once prayed for.

It is a message that holds two truths at once, the system may not be fair, and your effort still matters. If you are waiting to be discovered before you build your craft, you may wait forever. If you build anyway, you at least give life a target to hit.

The next chapter, and the challenge back home

Mills’ next chapter is personal, but he hopes its impact is collective. He wants people back home to look at his journey and recognize possibility: if someone who started with very little can come this far, then anything is possible.

At the same time, he places responsibility on both sides of the equation. He wants sponsors and government to recognize that art is powerful, deserving of respect and investment. He also wants artists on the island to keep dedicating themselves to the craft, putting in the hard work needed to elevate the creative community and earn that respect.

It is a full circle argument, and it lands because it does not let anyone off the hook. St. Maarten should not wait until its artists leave to decide they matter. Artists should not wait until they are funded to decide they are serious. The country and its creatives rise fastest when belief becomes policy, and policy becomes practice.

That is the deeper meaning behind a Super Bowl halftime appearance from a St. Maarten dancer. It is not only proof of individual excellence. It is also a mirror, asking what kind of island St. Maarten wants to be for the next Jay Mills, the one still learning from a screen, still rehearsing in borrowed spaces, still talented enough to go global, and still waiting to see if home will recognize them before the world does.

Join Our Community Today

Subscribe to our mailing list to be the first to receive

breaking news, updates, and more.

.jpg)